Culturally, we are almost post post-modernism. It is becoming increasingly clear that post-modernism did not work. Anecdotally I hear expressions of confusion and lostness. It’s like we came adrift from the past and we are floating around in a sea of debris trying to make sense of it all. We are confronted with multiple mashups without reliable tools for discerning which to engage with and which to discard. Approaching Buddhism, mindfulness and meditation is now like this too. How do we know what will work and what will not?

One approach is to understand where ideas and methods came from and how they got to be like they are. Understanding practice lineages makes it possible to relate to specific practices meaningfully. It is always useful to ask: How is a method supposed to function? What is the supposed result? How does that work in practice? Understanding how practices became the way they are helps in knowing whether or not they are still relevant.

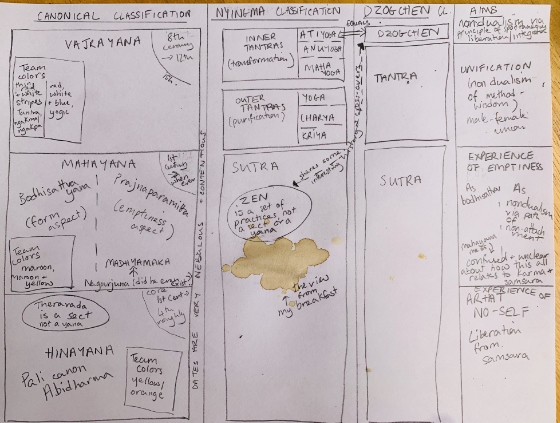

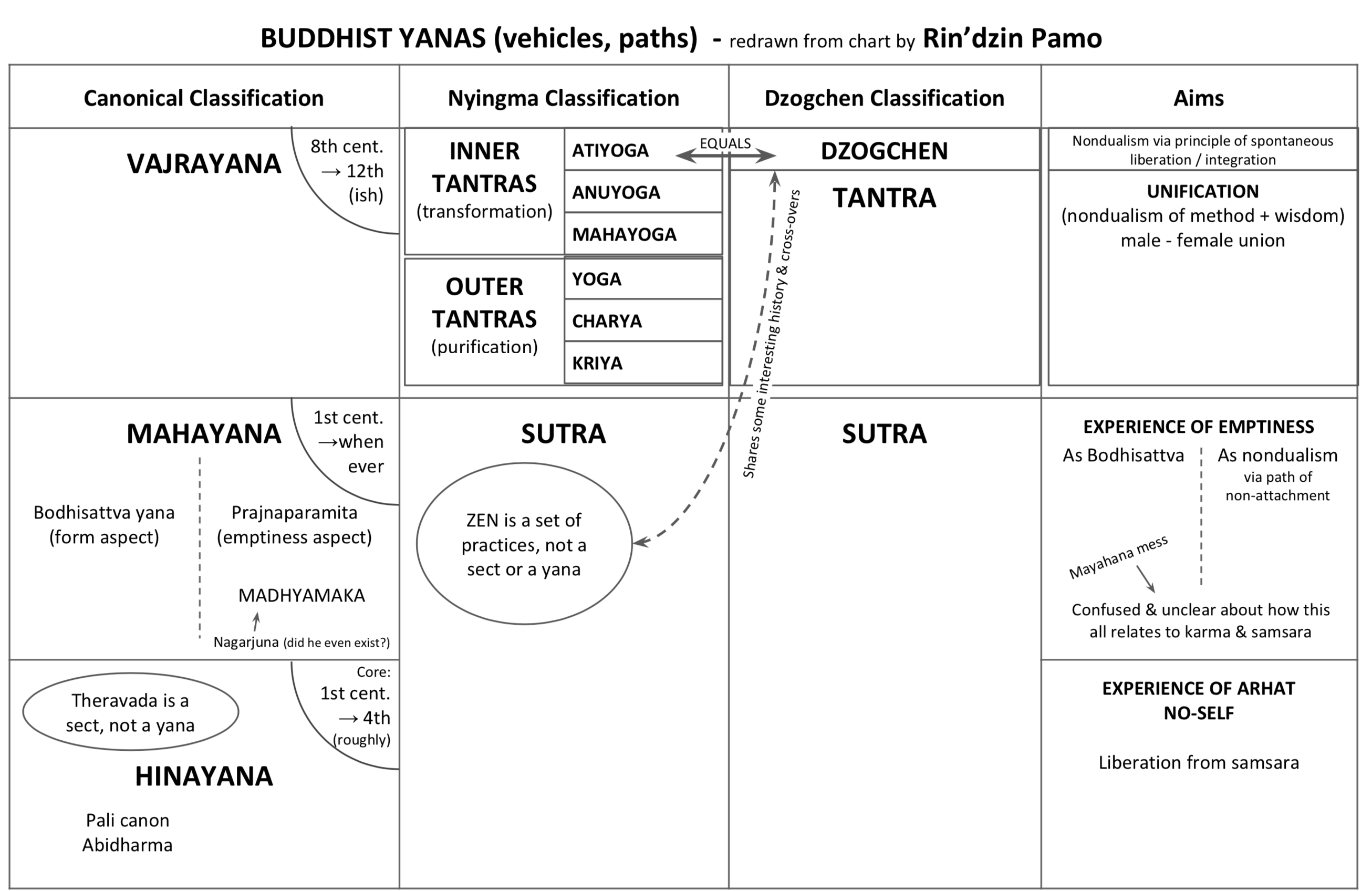

I made the chart above during some twitter conversations to help explain the variety of different practice lineages in Buddhism. The tweets below lead to discussions about how different types of Buddhism relate to each other, and what they might mean for personal practice. There are quite a few tangents. If you are interested you can follow some of them up on Twitter.

This one leads to a conversation with my friend @xuenay about the movement between renunciative and non-renunciative worldviews:

Yes: when Sutra/renunciation is your yana (path/worldview) that’s right, it would make no sense at all. But Tantra is meta to Sutra, by definition, so when Tantra is your overarching worldview, Sutra is ‘object’ - ie, you can approach it as a method.

— Charlie Awbery (@_awbery_) April 18, 2019

The following links to a conversation with many tangents about how different parts of Buddhism relate to each other:

Realized today I really don't have a good map of the different schools of Buddhism. Found this excellent chart by @Meaningness differentiating Sutra & Tantra. Now wondering:

— Malcolm 🙃cean (@Malcolm_Ocean) April 19, 2019

• Tantra = Vajrayana ?

• Sutra = {Mahayana, Theravada} ?

• what else is there?https://t.co/O0doNbHDI2 pic.twitter.com/z1H0rViuSu

A Dzogchen categorization of Buddhist paths

One way to map Buddhism is by categorizing it into Sutrayana, Tantrayana and Dzogchen. These are distinct paths. They have different starting points, methodology and results, and the language used to describe how their practices work is distinctly congruent with the worldview of each. This is a relatively late categorization. It views Buddhist practice from the perspective of its multiple paths. View is a key factor in determining how a method functions.

I like this particular categorization not only because it regards all practice in terms of its functionality — though that is reason enough. Uniquely it also presents Buddhist Tantra in a category of its own. From this perspective, Tantra is a ‘complete’ system in and of itself. It stands alone. This means we can approach Tantric practice on its own terms, using a language singularly appropriate to its principle and purpose, without indirection.

Sutric practice, when described in terms of its purpose, centers on liberation from samsara, the cycle of habitual grasping to attraction, aversion and indifference that causes suffering. The path is renunciative.

Tantric practice focuses on turning unhelpful, distorted emotions and behavior into well-aligned, practically useful responses. The path is transformative.

Dzogchen practice is spontaneous, congruent activity based in nondual perception. The path is liberative.

Sarah McManus referred to the chart I made during the tweetstorm breakfast in subsequent conversations. It also proved helpful in describing one aspect of Evolving Ground’s metasystematic approach to contemporary Vajrayana practice. Because it was proving handy for us, Sarah made a very nice, professional-looking version:

Buddhist yanas pro version courtesy Sarah McManus